Mary, Queen of Romania, born as Maria Alexandra Victoria of Saxa-Coburg and Gotha (October 29, 1875, Eastwell Park, Kent, England, July 18, 1938, Sinaia Pelişor, Kingdom of Romania), was princess of Great Britain and Ireland and the consort of King Ferdinand. Her memoirs are an important source of informations including medical ones, but also a surprising literature, which proves a writerly talent. Our approach aims at an incursion into the medical informations contained in the memoirs of Queen Marie of Romania, to our knowledge being the first attempt of its kind.

An event that occurs during the convalescence of the Crown Prince gives us the opportunity to bring to attention an important name not only in the medical world, but also in artistic life: „A tragic incident and totally unexpected appeared in our house (…) dr. Kremnitz, which was intended to remain with us until the full recovery of the Prince, died suddenly one morning because his heart stoped. (…) After the death of Dr. Kremnitz, doctor Romalo entered into our lives, he was our doctor until the end of his days” [1, p 141,142].

With Dr. Kremnitz, Mite Kremnitz appeared on the fashion and cultural scene of Romania at the end of the nineteenth century. Born as Marie Charlotte von Bardeleben, daughter of the famous surgeon Heinrich Adolf von Bardeleben, she spent her childhood in Greifswald, London, and since 1868 in Berlin. In 1872, at 20 years, Mite married Wilhelm Kremnitz.

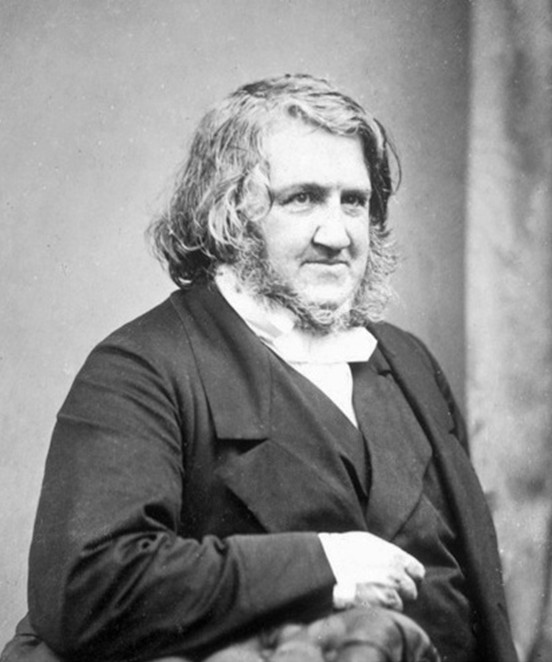

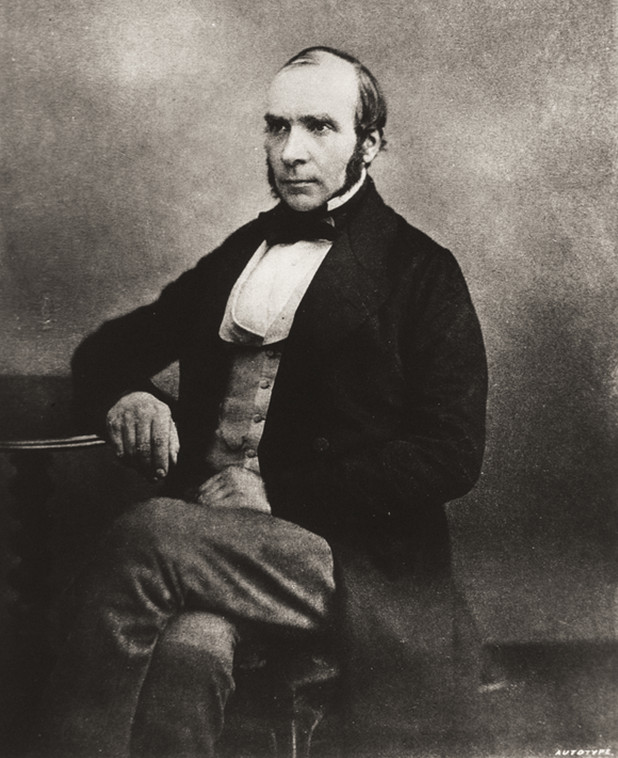

Heinrich Adolf von Bardeleben (1st March 1819-24th September 1895)

An event in the life of Titu Maiorescu will permanently link him with Kremnitz family: on the way to Paris, he will make a stop in Berlin in October 1859. Visiting the Kremnitz family, he gives them „some gourmet gifts”, which, as he says, he brought from „the Orient”. In the thirteenth day of staying in Berlin, the unexpected happens: in the day of departure to Paris, in the dark, he falls into a pit on a Berlin street and sprains his ankle, being forced to stay in bed. The Kremnitz installs him in a room in their house and begun caring for him, also calling a doctor for him. Maiorescu was the French language teacher for the four children of the family Kremnitz, including his future wife, Clara. In a letter of November 1859 from Paris, he will motivate the subsequent decisions: „In Berlin I spent three weeks, definitely the happiest time of my life. Every day I stayed in the family of the Chancellor of Justice Kremnitz, so every day I stayed with Clara. Fortunately, I sprained my foot and had to lie in bed after that, for eight days (…) In short, I will marry Clara„.

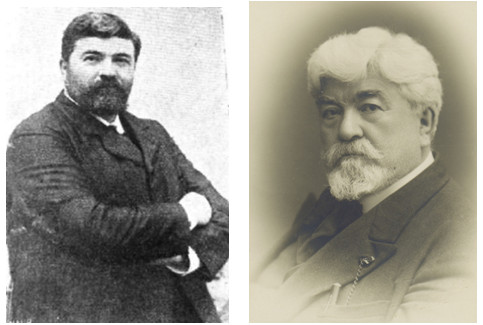

Titu Maiorescu in youth 1882 (left) and to maturity

From the marriage with Clara Kremnitz, Titu Maiorescu had two children: a daughter, Livia, and a son, Liviu.

At the invitation of Titu Maiorescu, Mite and Wilhelm Kremnitz traveled in 1873 to Romania, in Iasi, and in January 1875 the couple is established in Bucharest. Wilhelm Kremnitz opens a medical practice, becomes secondary doctor and then, in 1889, senior physician at Brâncovenesc Hospital [2]. During the War of Independence Dr. Kremnitz coordinates a military hospital installed in Cotroceni Station. He is becoming more and more popular, and become the doctor of the Royal family of Romania, following the path of his mentor and of his father-in-law, who was very appreciated by Kaiser Wilhelm I and was the doctor of the German Emperor, Frederick III.

The family ties with Maiorescu, the close link with the Royal family, Mite Kremnitz being the Lady of company of Queen Elizabeth, and the literary talent of Mite, facilitated their entry into the intellectual world of Bucharest. Mite Kremnitz attended the literary meetings of the Junimea (a famous literary Circle of that time) where she met Eminescu, Jacob Negruzzi, Ion Slavici, Nicolae Gane, Theodor Rosetti and Petre Carp [3].

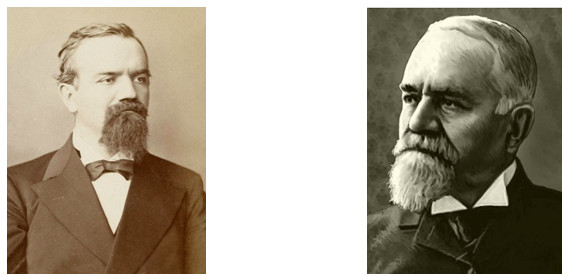

Mihai Eminescu in the last known photo (left) and at maturity (right)

Eminescu came to Bucharest as editor at the Time newspaper. Because the poet experienced great material difficulties, he gives private lessons of Romanian language to Mite Kremnitz. Mihai Eminescu becomes an intimate of Kremnitz family, being invited each year to spend Christmas holidays here. They were seeing home at Maiorescu, at the literary club Junimea and more than once, at the Royal Palace, where Queen invites Eminescu despite the cold relationship that he had with King Carol, who was severely critisized in his articles in the Time.

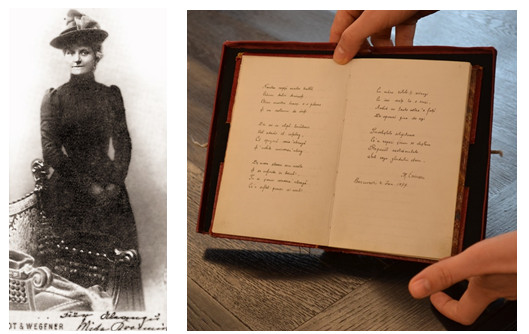

Mite Kremnitz and the famous red book

Mite Kremnitz’s great grandson, Georg, donated to the Central University Library of Cluj the famous „red book” which contains the poems transcripted by Eminescu for Mite, offered in January 4, 1879 as a gift for her birthday. The manuscript contains five poems in the poet’s version plus four more in the same book, copied by Mite [4].

Mite Kremnitz translated Eminescu’s poems „Desire”, „Over peaks” and it seems that also the „Morning Star” to German, she published a collection of Romanian tales, and she translated poems and prose of Queen Elisabeth (who used the literary pseudonym Carmen Sylva). She wrote plays and novels together with Queen Elizabeth, which they have signed with the pseudonym Ditto und Idem. She collaborated with King Carol I of Romania in writing of his Memoirs, in the collection donated by her great grandson existing a large number of files, apparently written by Carol I.

Wilhelm and Mite Kremnitz had two sons: Georg-Titus, born in 1876 in Bucharest and Emanuel (Manoli), born in 1885 at Peleș [5]. About the two children of Mite’s it was stated that they were conceived with Titu Maiorescu (Georg) and respectively with King Carol I (Emanuel). It is also said that the first name of Maiorescu, Titu, he wanted to put him in the Latinized form, so as he often signed, „Titus”, to his illegitimate child, Georg [6].

Wilhelm Kremnitz died on 31 July 1897 at Peleș and was buried on the royal domain, near the waterfall Urlătoarea, subsequently his tomb was moved to the park of the town.

Wilhelm Kremnitz’s tomb

According to Queen Mary, Mite, which the Queen never nominated her name, only as Dr. Kremnitz’s wife, wrote the book „The Court of Ragusa” in which she describes, parodying, the life of the Royal Court of Romania, to the disappointment of Queen Mary, one of the reasons why her presence is indicated briefly and superficially in the Queen’s memoirs: „It was a big news when lady Kremnitz has arrived from abroad to her husband’s funeral. Although Aunty (our note- Queen Elizabeth) had enough reasons not to love her, she received her as a person of the family. These two women resemble in a strange way. Both were writers, both had gray hair, short cut, with eyes in deep eye sockets, and thoughtfully (…) A few years earlier, they had written together a book in the form of letters exchanged between two friends. The collaboration was interesting and no doubt this united them for a time in the same enthusiasm, but this happened before my time, and I knew that now, Aunty has no love for the lady Kremnitz in her heart. The break, it seems, was made when Uncle (our note – King Carol I) had asked Mrs. Kremnitz to help him writing his memoirs, instead of asking this to Aunty, also a poet and writer. (…) Later, her innate meanness came out stronger when, in a unworthy way, she revenged against the royalty, who had once been her collaborator, writing a bad novel and also a vulgar one, titled The Court of Ragusa, in which, through changing the name of the people and of places, she describes in the form of parody the Aunty’s quirks and made a malicious description of the Court and her customs. Mrs. Kremnitz, of course, with a changed name, play in that novel the role of an intelligent woman, who is the confidence of the king and who straightened the queen’s mistakes. It is a book worthy of contempt” [1, p 142,143].

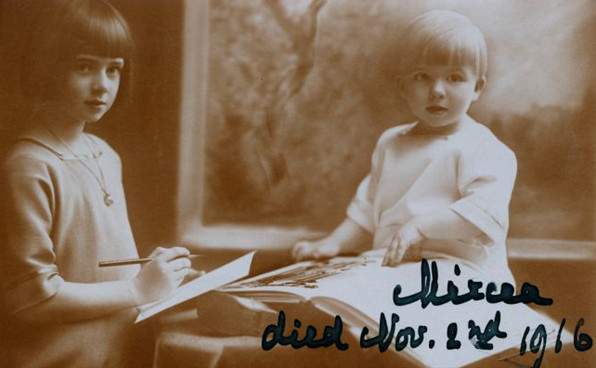

Elisabeth with her daughter Maria (called in family as Itty, 1870-1874). Photo from 1873

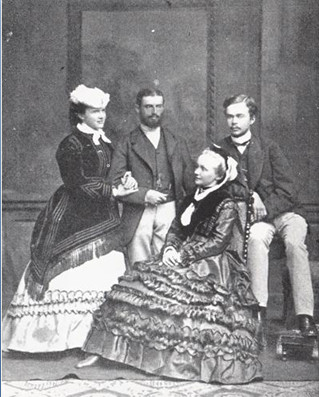

The Engagement Photography, 1869: Elizabeth of Wied, Prince Carol I of Romania (born as Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen), Mother-Princess Maria of Wied, Prince William of Wied (brother of Elizabeth)

In the 1899’s codicil of his testament, written in December 1911, Carol says: „The sons of Dr. Kremnitz will receive each forty thousand lei as gift and they will give of this sum four thousand lei to their mother, whose pension of twelve thousand, will be payed as so far, until her death„. Although her life in Romania was assured, with the annual rent paid by King Carol I – the equivalent of over 111,000 lei today – after her husband’s death, Mite Kremnitz prefered to return to Berlin, considering that the possibilities of giving her children a good education are more favorable in the German Empire. It is also interesting the further link of Mite sons with Romania, Georg-Titus attending a school of officers, and Emanuel medical studies. The two are enrolled in the Imperial Army and enter in Romania in 1918 with the occupation troops of the Central Powers. Georg-Titus Kremnitz, as officer of Staff of the German Army, is part of the delegation which proposes to Maiorescu, who, ironically, it seems that was his natural father, to form a government of occupation, anti-dynastic, proposal which he refused. On the other hand, however, he allowed the recovery of Slavic manuscripts of Academy Library Fund, documents requisitioned by the Bulgarian army, being in the process to be transported across the Danube [7]. Also, the Captain Emanuel Kremnitz, the supposed son of Carol I, although he was for a period of time the head of the censorship, is the one who saved in 1916 the archive of B.P. Hașdeu from Campina.

Mite Kremnitz passed away on July 18, 1916. She is the heroine of Eugen Lovinescu’s biographical novel, „Mite”.

References

- Maria, Regina României. Povestea vieţii mele, Ed. RAO, Bucureşti, 2013, Vol II, pag 140, 141-143.

- Nuţă I. Prefaţa la romanele Mite şi Bălăuca de Eugen Lovinescu, vol. 20 din Colecţia Eminesciana, Editura Junimea, 1980.

- Todescu V. Mite Kremnitz şi Junimea, Annales Universitatis Apulensis Series Philologica, v. 2, 2006.

- Hângănuț R. Povestea „Caietului Roșu” manuscrisul eminescian aflat în posesia BCU, Transilvania Reporter, 15 ianuarie 2014.

- Kremnitz G. Mite Kremnitz und ihre rolle in den deutsch-rumäniscgen Beziehungen, in Rumänien und Europa: Transversale: Kolloquium der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Rumänischen Kulturinstitut Titu Maiorescu, Maren Huberty&Michèle Mattusch Editors, Humboldt-Universität Berlin, Frank & Timme GmbH, 2009, pp. 121-34.

- Popescu-Cadem, Titu Maiorescu în faţa instanţei documentelor, Bucureşti, Biblioteca Bucureştilor, 2004, pp 24-8.

- Tăbăraş S, Eroi „mărunţi”, Revista Luceafărul, 2, 2009.