“I believe that a man is what he remembers about himself. For example, I consider myself what I remember that I am. That’s why, sometimes, people are, apparently, exchangers.”

Nichita Stănescu

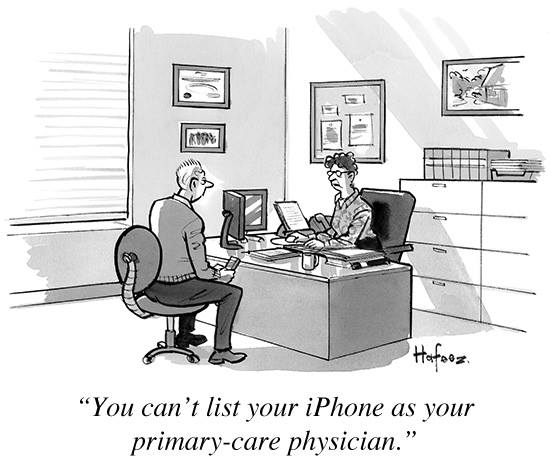

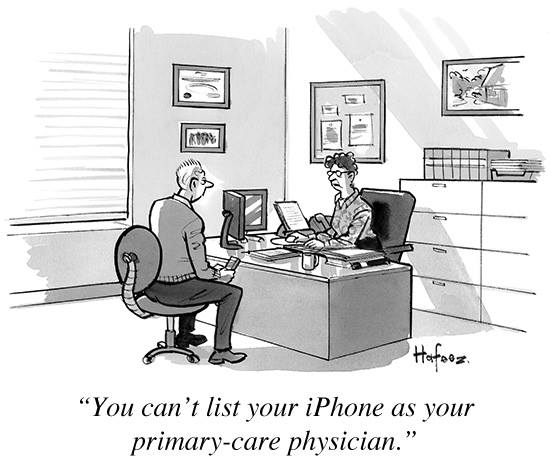

Medicine – anything and anyone?

„While healthy people instinctively tighten their ranks to form a community of people, intellectuals are running here and there like chickens in the poultry yard. With them you can not make history. They can not be used as elements to form a community.” Adolf Hitler, 1932.

„Let us take very decisive measures because it is a totally unsatisfactory situation. Political activity is needed too, to enlighten people, but first on the line of health is required that the health personnel, the doctors need to deal seriously of this and if they are not able to fulfill the tasks, they need to be replaced because their activity it is unsatisfactory. The doctors’ activity must be assessed after each birth he manages not upon abortions. The higher the number of abortions is so much his work should be regarded as unfit to perform.” Nicolae Ceauşescu, February 1984 [1].

„Gentlemen’s, I would ask you to observe a statement made very recently by one of the important member of the European Union and which begins to debunk the myth of doctors trained in Romanian universities. It is the newest statement coming from France who says frankly that Romanian doctors are poorly trained. Moreover, a presidential commission who assessed the health system in Romania shows that backfired in the diagnosis rate reached over 40% in the Romanian health system and is a result of the education system. That means that to a man who has an illness it is prescribed a recipe for another illness, a person that must not be operated is operated, so quality revolves around a highly sensitive area of daily life of citizens as a result of the quality of Romania’s education system.” Traian Băsescu, debate on the National Education Law, March 2010 [2].

Beyond antinomy of mutual perceptions, the sustainability of medicine and the often void character of politics, the temporary influence in public consciousness of the official statements is undeniable and also the frequency of return ideas from outside medicine, with claims of deep knowledge of medical phenomenon. The three declarations are made at large enough intervals of time, and from different political backgrounds, not to be suspected of being doctrinal inspiration, so proving socially psychological common roots.

Noam Chomsky, with the intuition of a former anarchist, established a list of “Ten Strategies for Manipulation” [3]:

- The strategy of permanent distraction, which is to divert public attention from important social issues, by the technique of flood or flooding continuous distractions and insignificant information.

- Create problems, and then offer solutions. This method is also called “problem-reaction-solution”. At first is created a problem referred to cause some reaction in the audience, so this will ask for the measures, exactly the ones established in advance, to be accepted.

- The “gradual” strategy. For the public to accept an unacceptable measure, it is enough to just apply it gradually, dropper, for consecutive 10 years.

- The strategy of deferring is to present an unpopular decision as “painful but necessary”, gaining public acceptance at the time, for future application. It is easier to accept a future sacrifice then one of immediate slaughter. This gives the public more time to get used to the idea of change and accept it with resignation when the time comes.

- Go to the public as to a little child. “If one goes to a person as if he had the age of 12 years, then, because of suggestion, he tends with a certain probability that a response or reaction also devoid of a critical sense as a person 12 years.”

- Use the emotional side more than the reflection for causing a short circuit on rational analysis, and finally to the critical sense of the individual.

- Keep the public in ignorance and mediocrity. The quality of education given to the lower social classes must be as poor and mediocre as possible so that the gap of ignorance that separates the lower classes from upper classes is and remains impossible to attain for the lower classes.

- To encourage the public to be complacent with mediocrity.

- To replace the revolt with self-blame. To let individual blame for their misfortune, because of the failure of their intelligence, their abilities, or their efforts.

10.Getting to know the individuals better than they know themselves.

Physicians must preserve their role and place in society, otherwise a desire always confirmed out by history and always questioned by the political class. Times seem to be always close to the „end of history”; or 2011 seems not any further, as the year of 1000 seemed not. Maybe now, there are many who hope and less those who waived.

References

- Doboş C (coord), Politica pronatalistă a regimului Ceauşescu. O perspectiva comparativă, Ed. Polirom, 2010, p348

- http://www.romanialibera.ro/actualitate/educatie/basescu-absolventii-de-medicina-sunt-slab-pregatiti-181729.html

- http://www.scribd.com/doc/43992243/Top-10-media-manipulation-strategies-by-Noam-Chomsky